This past week’s Zaller Law Group masterclass on AI in the Workplace walked California employers through what they need to know right now about AI in the workplace. The conversation covered everything from a federal court ruling on AI and attorney-client privilege to California’s new automated hiring regulations to practical tools employers can start using today.

Here is a recap of five key takeaways every California employer, CEO, business owner, HR professional, and in-house counsel should be thinking about on how AI will impact their business:

1. The AI Revolution Is Happening Right Now — And the Window to Adapt Is Closing

We opened the masterclass with a reference to an article by Matt Schumer, CEO of Otherside AI, that has gone viral in the AI community. Schumer has spent six years building in the AI space, and his message is blunt: the gap between what insiders know is coming and what the general public understands has gotten too wide to keep sugar coating.

His comparison that stuck with me is this: we’re in a moment similar to February 2020, right before COVID. Most people weren’t paying attention, and then three weeks later the entire world changed. The pace of AI development is staggering. In 2022, AI couldn’t do basic math. In 2023, it passed the bar exam. By 2024, it was writing software and explaining graduate-level science. In late 2025, some of the best engineers in the world said they were handing over most of their coding work to AI. And the CEO of Anthropic has publicly predicted AI will eliminate 50% of entry-level white-collar jobs within one to five years.

Even if you think those predictions are overblown, here’s what matters for employers right now: if AI stopped developing today, it has already changed the competitive landscape. Businesses that are leaning into it are operating more efficiently, making better decisions, and gaining advantages over those that aren’t. The window to get ahead of this curve is closing fast.

What to do: Sign up for paid AI subscriptions—Claude Pro, ChatGPT Plus, or the $100 Pro plans if your budget allows. The difference between free and paid models is dramatic. Stop treating AI like a search engine. Push it with real business tasks you don’t think it can handle, and you’ll be surprised by what comes back. And build the habit of staying current—this technology is changing week to week.

2. Your AI Conversations Are Not Confidential — A Federal Court Just Made That Clear

One of the most important legal developments we covered is U.S. v. Heppner, a federal case out of New York that is making its way around the legal community. A CEO charged with fraud was using Claude to research his own criminal case. The FBI seized his computer, and when prosecutors sought access to his AI chat history, his attorneys objected, arguing the conversations were protected by attorney-client privilege.

The court disagreed. Chatting with an AI platform about legal issues does not create a confidential attorney-client relationship, and the content is not privileged. Users should treat AI like any other research tool—no different from typing a legal question into Google or drafting notes in a Word document. If it’s not a communication with your actual attorney, it’s not privileged.

This has significant implications for employers. When your HR team is using ChatGPT to figure out how to handle a performance issue, those conversations could be obtained by an opposing party in discovery. It feels private when you’re chatting with AI, but it isn’t.

There is a narrow opening the court left: if an attorney directs a client to perform AI research as part of the attorney’s work product, there could be an argument for protection. But that’s untested and narrow. On the flip side, AI chat history could also help justify employment decisions. If an HR professional used AI to research how to coach an underperforming employee—focusing on business reasons and best practices—that could be evidence the employer was focused on legitimate, non-discriminatory reasons.

While some AI software provides “incognito” modes, this does not make the conversations private, and there still is likely a record of that chat. AI providers may still retain data for 30 days or longer, even when incognito is enabled. Much like a Google search, that data is going to be out there somewhere.

What to do: Treat AI conversations like any other company document—assume they are discoverable. If you’re handling truly confidential information, use a private system like Microsoft Copilot tied to your organization’s secure environment, not a public-facing platform. And develop an AI usage policy that makes clear to employees what can and cannot go into public AI systems.

3. California’s AI Hiring Regulations Are Already Here — And More Are Likely Coming

California already has regulations on the books governing AI in hiring. In October 2025, the Civil Rights Council issued regulations explaining that employers are liable for discrimination arising from automated decision systems (ADS) used in the hiring process.

The core principle is straightforward: existing discrimination laws apply when you use AI in hiring. You cannot deflect liability by saying “the software did it.” If your AI screening tool filters out candidates based on a protected characteristic—race, gender, age, disability, national origin—you are responsible, not the vendor. The definition of ADS is broad and covers many different tools that employers can use in the hiring process, such as any software that prioritizes, ranks, or filters candidates.

And the Legislature is potentially adding new AI-employment related laws in 2026. SB 947 proposes additional requirements for automated decision systems. SB 951 would require employers who displace an employee because of technology adoption to provide at least 90 days’ advance notice. These bills are making their way through the California State Legislature right now.

There is also a federal issue. The Trump administration has signaled interest in preempting state-level AI regulation to prevent a patchwork of 50 different state frameworks, which the AI industry strongly opposes. Whether federal preemption actually happens remains to be seen, but California employers need to comply with what’s on the books today.

What to do: Audit your hiring process now. Identify every tool that touches candidate screening, ranking, or selection—including applicant tracking systems and resume-screening software. Build transparency clauses into your vendor contracts. And most importantly, maintain a human in the loop for all hiring decisions. Don’t abdicate decision-making to software.

4. Your Data Is Your Greatest Asset — Use It Before Opposing Counsel Does

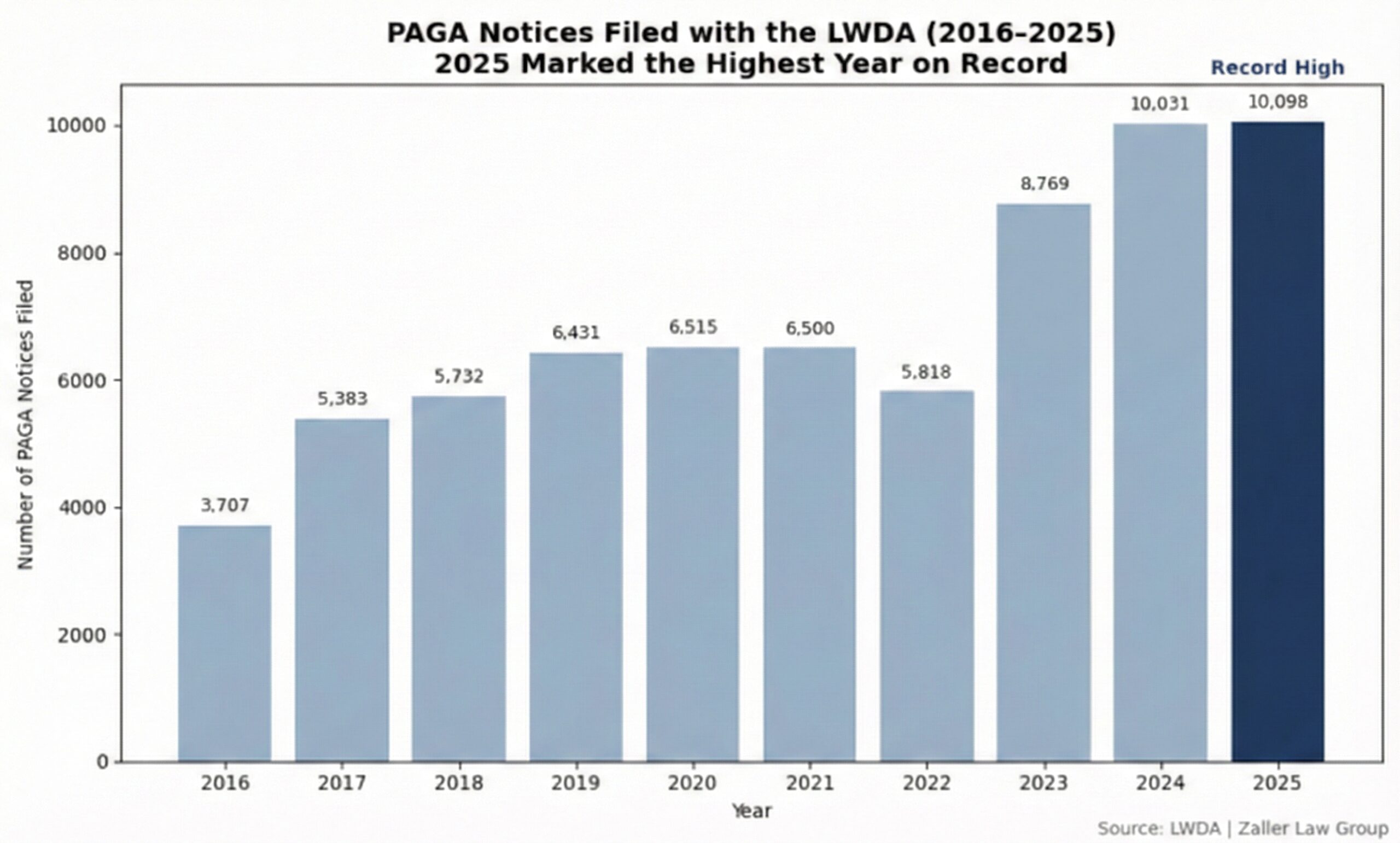

California employers don’t have many advantages when it comes to employment litigation, but here’s one they often overlook: their own data. Your time records, payroll data, break logs, and scheduling records are not just administrative paperwork—they’re evidence that can either protect you or sink you in a PAGA case, class action, or wage and hour claim.

We walked the masterclass through Scaled Comp, a software tool we developed out of a real litigation pain point. For years, when a PAGA case or class action came in, our paralegals and support staff would spend weeks manually analyzing time records—often across scattered formats like PDFs, CSVs, and sometimes even paper records going back years. We’d take a sample and extrapolate. That’s how most firms still do it.

Scaled Comp can now review the time records and produce a comprehensive analysis in days rather than weeks. It reproduces time entries in easy-to-read format, flags shifts with potential meal and rest break issues, and provides business intelligence into employer’s wage and hour compliance.

But the bigger point for employers is this: after the 2024 PAGA reform, employers who can demonstrate they took “reasonable steps” to comply can cap penalties at 15% of the maximum. One of the most powerful ways to show “reasonable steps” is proactive time record auditing. If you’re running monthly or quarterly meal break audits, and a PAGA letter arrives, you’re not scrambling—you already know where you stand.

What to do: Know your data before opposing counsel forces you to. Run proactive compliance audits on your time records—at minimum quarterly. Understand where your meal and rest break compliance stands across every location and every manager. Store your data properly and think about how you’ll use it defensively. And if a PAGA letter arrives, get your data analyzed immediately rather than going to mediation without understanding your actual exposure.

5. AI Can Transform Your Employee Training and Compliance Programs — Starting Today

Employers can take their meal and rest break policy and have AI repurpose it into formats employees can fully engage with. It can simplify legal language into plain English. It can create quizzes for training sessions. Tools like Google’s NotebookLM can convert written policies into podcast-style audio that employees can listen to on their own time.

Compliance isn’t just having a policy—it’s making sure employees actually understand it and can access it in a format that works for them. And from a litigation defense perspective, being able to show that you didn’t just have a policy but that you actively trained on it, reinforced it, and made it accessible in multiple formats is powerful evidence of “reasonable steps” under the PAGA reform.

What to do: Start with one policy—meal and rest breaks is a great place to begin. Record a five-minute best-practice demonstration and use AI to turn it into reusable training content. Build a library over time. And think about your employees as an internal audience that needs to be marketed to—because the more they understand your policies, the more defensible your organization becomes.

The Bottom Line

AI is not coming to the California workplace—it’s already here. Your employees are using it whether you have a policy or not. California regulators are already holding employers accountable for how AI is used in hiring. And the federal courts have made clear that your AI conversations are not confidential.

But this is not just a story about risk. Employers who lean into AI strategically—who use it to train employees, audit compliance, analyze their data, and strengthen their litigation posture—are going to be in a fundamentally stronger position than those who ignore it or try to ban it. The employers who engage with this technology now, with eyes open and proper guardrails in place, will have a significant competitive advantage.