Recently we have been litigating and answering basic issues about employers’ obligations to provide meal and rest breaks. It has been a few years since the California Supreme Court issued its groundbreaking ruling in Brinker Restaurant Group v. Superior Court, and there is no indication that wage and hour litigation for California employers will lighten up, so employers should constantly monitor and audit their meal and rest break policies and practices. Here are five reminders for employers:

1. Timing of breaks.

Meal Breaks

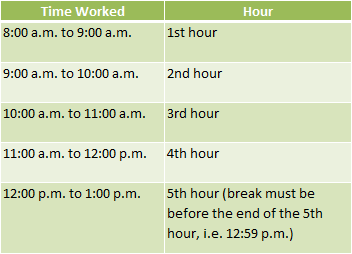

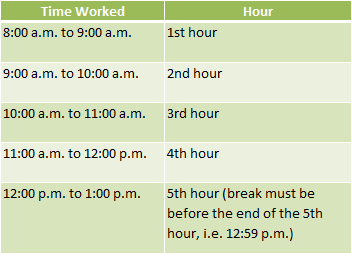

The California Supreme Court made clear in Brinker Restaurant Group v. Superior Court that employers need to give an employee their first meal break “no later than the end of an employee’s fifth hour of work, and a second meal period no later than the end of an employee’s 10th hour of work.” Here is a chart to illustrate the Court’s holding:

Rest Breaks

As for rest breaks, the Court set forth that, “[e]mployees are entitled to 10 minutes’ rest for shifts from three and one-half to six hours in length, 20 minutes for shifts of more than six hours up to 10 hours, 30 minutes for shifts of more than 10 hours up to 14 hours, and so on.” This rule is set forth in this chart:

In regard to when rest breaks should be taken during the shift, the Court held that “the only constraint of timing is that rest breaks must fall in the middle of work periods ‘insofar as practicable.’” The Court stopped short of explaining what qualifies as “insofar as practicable” and employers should closely analyze whether they may deviate from this general principle.

2. Rule regarding waiver of breaks.

Meal Breaks

Generally meal breaks can only be waived if the employee works less than six hours in a shift. However, as long as employers effectively allow an employee to take a full 30-minute meal break, the employee can voluntarily choose not to take the break and this would not result in a violation. The Supreme Court explained in Brinker (quoting the DLSE’s brief on the subject):

The employer that refuses to relinquish control over employees during an owed meal period violates the duty to provide the meal period and owes compensation [and premium pay] for hours worked. The employer that relinquishes control but nonetheless knows or has reason to know that the employee is performing work during the meal period, has not violated its meal period obligations [and owes no premium pay], but nonetheless owes regular compensation to its employees for time worked.

Rest Breaks

Rest breaks may also be waived by employees, as long as the employer properly authorizes and permits employees to take the full 10-minute rest break at the appropriate times.

3. Timekeeping requirements of meal breaks.

Meal breaks taken by the employees must be recorded by the employer. However, there is no requirement for employers to record 10-mintute rest breaks.

4. Implementing a procedure for employees to notify the company when they could not take a break.

If employers have the proper policy and practices for meal and rest breaks, the primary issue then becomes whether the employer knew or should have known that the employee was not taking the meal or rest breaks. Therefore, allegations that the employer was not providing the required breaks can be defended on the basis that the employer had an effective complaint procedure in place to inform the employer of any potential violation, but the plaintiff failed to inform the employer of these violations.

5. Time rounding for meal breaks is not permitted under California law.

In Donohue v. AMN Services LLC, the California Supreme Court held that employers may not use time rounding policies in context of meal periods, and time records for meal periods that are incomplete or inaccurate raise a rebuttable presumption of meal period violations. The Court explained that rounding polices when used for meal breaks, an employee’s 30-minute meal break could lose 9 minutes due to rounding, which amounts to nearly a third of the meal break. If an employee is not provided a full 30-minute meal break because of rounding, there is no mechanism that makes up for the premium pay owed to the employee that would average out over time. The Supreme Court held, “The precision of the time requirements set out in Labor Code section 512 and Wage Order No. 4 — “not less than 30 minutes” and ‘five hours per day’ or ‘ten hours per day’ — is at odds with the imprecise calculations that rounding involves. The regulatory scheme that encompasses the meal period provisions is concerned with small amounts of time.”

California Labor Code section 226.7 provides that employees are entitled to receive premium wages in the form of one additional hour of pay at the employee’s regular rate of pay for a missed meal or rest break.

California Labor Code section 226.7 provides that employees are entitled to receive premium wages in the form of one additional hour of pay at the employee’s regular rate of pay for a missed meal or rest break. Walgreens. The appellate court’s decision provides a few good lessons for employers defending class action allegations.

Walgreens. The appellate court’s decision provides a few good lessons for employers defending class action allegations.